Executive Summary

Illicit antiquities, some pilfered from war zones where jihadist groups operate, are increasingly finding their way online where they are being snapped up by unknowing buyers and further driving the rampant plunder of archaeological sites.

These internet sales are spurring a vicious cycle: increasing demand for antiquities, which drives the looting, producing a greater supply of artifacts, which further increases demand.

While global auction sales of art and antiquities declined in 2015—falling as much as 11 percent—online sales skyrocketed by 24 percent, reaching a staggering $3.27 billion dollars.[1] According to Forbes, “This suggests that the art market may not be cooling, exactly, but instead shifting to a new sales model, e-commerce.”[2]

How can an online buyer guarantee that a potential purchase is not stolen property, a “blood antiquity,” or a modern forgery? The best protection is to demand evidence of how the object reached the market in the first place. However, as in more traditional sales, most antiquities on the internet lack any such documentation.

Online shoppers therefore have limited means of knowing what they are buying or from whom. This is a particularly serious concern given the industrial scale looting now taking place in Iraq and Syria, which the United Nations Security Council warns is financing Daesh (commonly known as ISIS, ISIL, or Islamic State), al Qaeda, and their affiliates.

Despite the clear implications for both cultural preservation and national security, so far public policy has completely failed to regulate the online antiquities trade. This is particularly true in the United States, which remains the world’s largest art market and a major center for the internet market in antiquities.[3] American inaction has made it impossible to combat the problem globally, and moreover, is in great contrast to positive steps taken by other “demand” nations like Germany.

This paper offers practical solutions to help better protect good faith consumers from purchasing looted or fake antiquities—while also protecting online businesses from facilitating criminal behavior. After briefly reviewing what is known of the organization and operation of the internet market in antiquities, it considers some possible cooperative responses aimed at educating consumers and introducing workable regulation. These responses draw upon the German example, as well as recent criminological thinking about what might constitute effective regulation. Finally, the paper makes seven policy recommendations, which while geared towards the American market, are applicable to any country where antiquities are bought and sold online.

Introduction

Antiquities have been trafficked internationally since the time of the eighteenth-century “Grand Tour.” They are clandestinely excavated from archaeological sites or forcibly removed from architectural remains, and then traded to be acquired by private and institutional collectors worldwide. This trafficking damages and destroys cultural heritage, fosters criminality and corruption, and funds terrorism and other forms of armed violence.

The seriousness of the problems caused by the trade was recognized in 1970 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) when it adopted the Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, which recommended standards for national curation of cultural heritage and established a series of rules and diplomatic procedures aimed at controlling the illicit trade. As satellite images of devastated archaeological sites in Syria and Iraq so graphically show, however, antiquities trafficking is getting worse, not better. One reason for its persistence and continuing depredations has been the development of a wide-ranging internet market in antiquities.

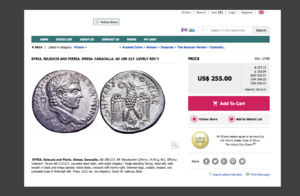

Since the launch of eBay in 1995, the internet market in antiquities has grown to be a sophisticated and diversified commercial operation. Alongside the continuing existence of eBay, which offers a platform enabling private (consumer to consumer) transactions through auction, more traditional (business to consumer) businesses have established themselves. These include companies selling directly to the public from virtual galleries (termed here internet dealers) and those offering material for online auction (termed internet auctioneers).

Also notable has been the appearance of internet malls or marketplaces, which gather together on one website links to a range of traders or “members,” all offering related types of material. Potential consumers can search or browse according to material or vendor. Trocadero, for example, links to the inventories of internet dealers in art and antiques, including antiquities; VCoins links to internet dealers in coins, including ancient coins. Invaluable and LiveAuctioneers among others provide a similar service for internet auctioneers.[4]

The Problem

As far back as 2006, the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL), UNESCO, and the International Council of Museums (ICOM) warned about the damaging effect of this burgeoning internet marketplace on the world’s cultural heritage. These institutions and other experts feared that the very nature of the online market would allow it to easily surpass the reach and scale of the traditional antiquities trade. Given the rules of supply and demand—and that the only source of genuine artifacts is a limited number of archaeological sites—this threatened an increase in antiquities looting and trafficking.

The ongoing situation in Syria has confirmed those worst fears. In 2016, for example, the International Center for Terrorism and Transnational Crime in Ankara announced that since 2011 Turkish authorities had seized 6,800 objects, the majority of them coins.[5] Trafficked coins and other small objects from Iraq and Syria are being sold openly and in great quantity on the internet.[6]

The internet allows for the participation of consumers from a much broader range of socioeconomic backgrounds than has previously been the case. For businesses and consumers both, the barriers to entry are much lower than in the past, when bricks and mortar shops were the norm. In fact this easy access actually works against traditional dealers who maintain physical galleries in expensive locations such as New York or London, and favors a new business model whereby large inventories can be stored in low-cost locations, yet sold around the world.

Online galleries and auction platforms thus bring geographically distant buyers and sellers together in electronic space and in the process make it financially viable to trade in low-value and potentially high-volume material. This means that minor archaeological sites or cultural institutions, which previously may not have been worth looting and thus left intact by criminals, can now be viewed in a more lucrative light and targeted accordingly. The resultant trade in small, portable, and easy to conceal antiquities is less likely to make headlines than that in major works of ancient art, but it is more difficult to police and arguably more destructive to the historical record. Finally, archaeologists, traders, and consumers alike believe the internet market to be riddled with fakes.[7]

Internet apps and social media are also offering new opportunities for criminals. For example, Skype and WhatsApp are being used by thieves and traffickers to arrange deals.[8] When on May 16, 2015, U.S. Special Forces raided the Syrian compound of Abu Sayyaf, the head of Daesh’s administrative section for the supervision of excavation and trade of antiquities, they discovered images of stolen antiquities in the WhatsApp folder of his cellphone.[9] It is becoming increasingly common to see antiquities offered for sale on sites such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube. It is also suspected that internet discussion forums might be used for such purposes.[10]

Certainly the one dependable constant of the internet market is that it is continually creating or adapting to new commercial opportunities. While the antiquities traditionally available for sale online have been low-end pieces or fakes, sold by anonymous or minor dealers, now the art world’s leading institutions are also seeing a chance to grow their consumer base. For example, the two major auction houses, Sotheby’s and Christie’s, have moved into internet trading. In 2015, Sotheby’s commenced live streaming some auctions on eBay, though does not yet seem to have gone down that route for antiquities. In 2011, Christie’s established its own online platform, and in October 2016, offered for sale forty antiquities deaccessioned from the Toledo Museum of Art. The success of this sale could open the door to other such auctions in the future, further and significantly changing the face of the online antiquities marketplace. The participation of old and trusted companies like Christie’s and Sotheby’s will improve consumer confidence in online sales more generally.

It is suspected that the darknet is being used to transact trafficked antiquities, but no evidence has been produced. One explanation may be that there is no need to use the darknet when trafficked antiquities can be sold openly on publicly accessible websites with seemingly little risk to the vendors. Between 2007 and 2010, working with Salvadoran police, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents cracked open a smuggling racket moving Salvadoran antiquities into the United States for sale on eBay, seizing and returning dozens of objects.[11] But investigations such as this one are rare, and convictions rarer still.

Risk For Consumers

As well as encouraging the looting and trafficking of the world’s cultural heritage, the online antiquities trade also poses a number of serious risks to consumers.

While an internet shopper may indeed be purchasing a real antiquity that was scientifically excavated in accordance with national law, and left its country of origin with a valid export permit, the odds are much greater of purchasing a trafficked or fake object. Again, buyers also risk the possibility of unintentionally supporting the organized criminals, armed insurgents, and violent extremist organizations who are known to deal in antiquities.

As mentioned above, a buyer’s best protection is demanding proof of provenance (an antiquity’s ownership history), or even better provenience (its “findspot” in an archaeological excavation). Verifiable information about provenance and provenience allows a clear chain of ownership to be traced between an object’s place of discovery and its sale, thus assuring its legitimacy and authenticity. When this chain is poorly recorded, and nothing is known of an object’s history, it is easy to pass off a stolen object as legitimate and a fake object as genuine. Yet even a cursory search of the internet demonstrates that most antiquities are sold online without any secure documentation of either provenance or provenience, and furthermore, both can easily be forged.

Several internet dealers do provide lengthy advice on their websites about avoiding fakes on the market while proffering questionable “guarantees of authenticity,” but have less to say about trafficking. For example, one internet dealer seems more concerned about arbitrary customs seizures than trafficking when warning consumers that:

Certain items listed on this site may be subject to various export/import laws and other laws of the United States and other countries. It is the buyer’s responsibility to obtain any relevant export or import licenses or other permits to ensure legal purchase, transport, and import of any item. We are not responsible for increasingly arbitrary customs seizures based on regulations of the purchaser’s country. Please check with your customs before ordering.

He is on firmer ground when reassuring consumers about the authenticity of his stock:

The authenticity of all pieces is fully guaranteed for as long as you own them. Any item shown otherwise may be returned unaltered for a full refund. A Certificate of Authenticity with printed color image is available for an additional $10 fee. Any item not to your satisfaction may be returned unaltered within 7 days of receipt for a full refund less shipping.

Statements such as these suggest sellers are trying to protect business by reassuring consumers about the authenticity of material offered for sale, while at the same time not frightening them off with talk of laws and law-breaking.

Yet laws and law-breaking should be of particular concern to online shoppers of ancient art in the United States, which again remains the world’s largest art market.

Under U.S. law—the National Stolen Property Act (NSPA), the Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act (CCPIA), and others—sellers, transporters, buyers, and even possessors of illicit antiquities may find themselves subject to a number of civil and even criminal penalties.

Additionally, under the CCPIA, the U.S. has bilateral agreements with sixteen nations, as well as emergency actions imposing similar terms for Iraq and Syria, which restrict the import of their antiquities into the United States. Antiquities that enter the country in violation of these agreements are subject to forfeiture.

Yet consumers appear to be undeterred by these many risks, judging from the size of the market. Buoyant sales figures suggest that consumers are either unaware of the possible illicit or fraudulent sources of material up for sale, or know and do not care. Thus the internet market is flourishing in part because of widespread ignorance or indifference on the part of consumers to the issues involved.

Policy Recommendations

Poor consumer awareness is something that must be changed. As mentioned above, in response to growing concerns about the internet market, UNESCO, INTERPOL and ICOM issued a joint warning on the online trade in 2006. They recommended that the following disclaimer be posted on any website offering antiquities for sale:

With regard to cultural objects proposed for sale, and before buying them, buyers are advised to: i) check and request a verification of the licit provenance of the object, including documents providing evidence of legal export (and possibly import) of the object likely to have been imported; ii) request evidence of the seller’s legal title. In case of doubt, check primarily with the national authorities of the country of origin and INTERPOL, and possibly with UNESCO or ICOM.

Over a decade later, despite an extensive search by the author, this language is nowhere to be seen on websites offering antiquities for sale, and self-regulation appears to be largely non-existent.

As a first step towards improving the market, all internet sales websites should be encouraged to display in clear view an unambiguous statement about acceptable provenance similar to this one recommended by ICOM/INTERPOL/UNESCO. Such a clear view statement on sales websites about the problems associated with no provenance—and the measures necessary to establish good provenance—might in itself do something to change the complacent attitudes of consumers as regards the absence of provenance. Ideally, the requirement for such a statement should be established in law, though that seems unlikely in the United States due to public and political opposition to statutory trade control.

A voluntary strategy offers more promise of success. In particular, eBay has an unparalleled opportunity to improve consumer awareness, not just because it is a major player, but also because it is in its own interest to implement a solution. One reason for this is that antiquities sales account for only a very small part of its total turnover, so it might consider that avoidance of bad publicity and reputational harm would outweigh any financial loss incurred through frightening off consumers.

Apart from the obvious material benefit of alerting buyers to the problems associated with unprovenanced antiquities, eBay also offers a way of reaching out to the broader consumer base. People buying from eBay are likely to be buying from other sales sites. Thus clear statements on eBay alerting buyers to the legal requirements and damaging consequences of purchasing unprovenanced antiquities offer an otherwise unavailable means of informing consumers who are unaware of the issues involved. eBay policy statements can in effect be used as bulletin boards.

Yet, as of today, most eBay shoppers can search for and purchase an antiquity without any notice of the potential risks associated with purchasing unprovenanced antiquities. This is true despite the fact that eBay itself already does regulate the sale of antiquities through rules published in its policy statements about prohibited and restricted items. These vary slightly from country to country. In Germany, for example, a clear definition of an antiquity is provided and it is stated that an antiquity can only be offered for sale if accompanied by valid documentation of legal export from its country of origin. It is prohibited to sell any object listed on ICOM Red Lists, which illustrate and describe for the benefit of customs agents, traders and collectors types of objects that are at risk of theft and trafficking.

In the United States, antiquities are defined as “items of cultural significance … from anywhere in the world” and, it is stated that an antiquity can only be offered for sale if accompanied by an image (if available) of valid documentation of legal export from its country of origin. eBay’s German and U.S. written rules are broadly in line with the 2006 ICOM/INTERPOL/UNESCO recommendations. These rules are aimed at potential sellers, but could also alert buyers to what might constitute a genuine object and legitimate purchase.

Unfortunately, in the United States, not only are these rules generally unenforced, again they are not even visible to potential consumers. At present, from the eBay home page it is a four-click path starting from a small print policy heading at the foot of the page to the statement of regulations. From the same home page it is a separate four-click path to the antiquities sales pages. At no point do these paths intersect and it is possible for a buyer to reach the sales pages without needing to view the rules.

The United Kingdom is an exception. There eBay has instated a pop-up window for potential vendors of domestic antiquities advising them of legal requirements. This could serve as a model for other antiquities sales as well as other countries.

Ideally, across all eBay platforms, the sales regulations should appear in a pop-up window that has to be checked in acknowledgement by a potential buyer before proceeding to the sales pages. If that is not possible, it should be ensured that the click-path from home page to sales pages navigates through the statement of rules.

Raising consumer awareness in itself can only achieve so much. There will always be naïve or unaccommodating consumers looking for a bargain or a special piece and who are prepared to buy unprovenanced antiquities. Traders must be persuaded or induced to adopt and comply with regulations concerning provenance. To achieve this end, more needs to be done in terms of monitoring antiquities offered for sale.

Despite their similar rules on paper about the provision of provenance documentation, more antiquities are offered for sale without provenance in the United States than in Germany (for example, a quick search of eBay by the author revealed none offered in Germany, but hundreds in the United States). Indeed, most antiquities are offered for sale in the United States with no indications of provenance, while the reverse seems to be true in Germany. These different standards of regulatory compliance are likely due to the presence (in Germany) or absence (in the United States) of external oversight.

In Germany, monitoring and oversight are provided by state representatives of the Landesdenkmalpflege, legally mandated organizations within each state (Land) responsible for the protection and conservation of cultural heritage. In the United States, there does not appear to be an appointed responsible monitor of that sort. Thus the example of eBay USA shows that in the absence of effective oversight regulation is likely to fail. Concerned public or professional bodies such as the National Park Service, the Smithsonian Institution, or one of the major archaeological societies need to step up and respond to the challenge.

The German model is exemplary. The simple rule for non-domestic antiquities that an offered antiquity has to be accompanied by an image of valid export documentation should reduce to a minimum the time burden of monitoring. Clearly, documents can be forged, but only at increased risk to the trader. Creating false provenance is fraud, and puts traders at risk of indictment for fraud, which is easier to prove than theft, giving better opportunities to law enforcement.

eBay has shown itself in Germany to be amenable to an effective combination of regulation and external oversight. The situation with other internet dealers and auctioneers whose livelihoods are at stake is not so promising, as they are likely to refuse externally-monitored regulation. They might respond, however, to a more critical (and skeptical) consumer base. Encouraging consumers to buy from closely monitored and regulated eBay sales might draw business away from poorly regulated sales sites, and encourage some dealers or auctioneers at least to adopt similar policies of regulation and oversight.

Even in the absence of regulation, concerned organizations and individuals should be prepared to monitor internet sales for the presence of identifiably stolen or trafficked antiquities. In Korea, for example, the Overseas Korean Heritage Foundation monitors more than 4000 online auction houses, which are gathered on several marketplace platforms. It identifies between 20 and 200 Korean objects every week and notifies relevant national museums and police agencies. Since the monitoring program began in 2014, seven objects have been recovered.

Given the widespread criminality of the antiquities trade and its financial connections with organized crime and terrorism, criminal wrongdoing on the part of internet dealers or auctioneers should be prosecuted and punished. The emphasis should be on convicting criminals and removing them from the market. The seizure of material in itself does not exert a deterrent effect, it simply increases the cost of doing business (as demonstrated by attorney Ricardo St. Hilaire in his Antiquities Coalition Policy Brief “How to End Impunity for Antiquities Traffickers: Assemble a Cultural Heritage Crimes Prosecution Team”).

There have been a few convictions of people offering stolen antiquities on eBay, but they are the small fish of the antiquities market pond and their convictions have had no discernible material or deterrent effect. One or two high-profile and well publicized convictions for illegal trade with associated custodial sentencing might send a chastening message, alerting more upmarket dealers and auctioneers who choose to ignore warnings about the legal pitfalls of trading in unprovenanced antiquities, something that the poorly-publicized convictions of small-time eBay traders has signally failed to do. Without prosecution of criminal wrongdoing, the trade will persist.

Conclusion

The internet market in stolen and trafficked antiquities is having a destructive impact on cultural heritage worldwide. It appears to be largely out of control. A new policy aimed at improving consumer awareness in combination with measures of voluntary regulation and oversight supported by vigorous law enforcement when appropriate will encourage the emergence of a legitimate trade and go some way to ridding the internet of its scourge of trafficked and faked antiquities.

-

All internet sales websites should be encouraged and preferably required to display in clear view an unambiguous statement about acceptable provenance of objects sold, similar to the one recommended by ICOM/INTERPOL/UNESCO.

-

These websites should be encouraged and preferably required to display in clear view a warning about the prevalence of fake antiquities and explain why authenticity cannot be guaranteed without verifiable provenance and find spot and expert or scientific examination.

-

In the United States, these websites should be encouraged and preferably required to display in clear view an explanation of the governing U.S. law, including the relevant provisions of the Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act (CCPIA) and bilateral agreements or memoranda of understanding (MOUs). Sites should also consider including a link to the Cultural Property Protection page of the U.S. Department of State (http:// eca.state.gov/cultural-heritage-center/cultural-property-protection).

-

eBay, as the leading online auction platform, should take the lead in incorporating the preceding three recommendations into their policy statements about prohibited and restricted items.

-

Professional bodies or other independent organizations with the necessary authority and expertise should advocate for these recommendations, and moreover, be prepared in agreement with eBay and other online dealers and auctioneers to monitor sales regularly to ensure compliance.

-

These professional bodies/independent organizations should also be prepared to monitor other internet sales sites regularly to identify stolen and trafficked antiquities and work with law enforcement.

-

Criminal investigations of illicit trade should focus on the internet dealers and auctioneers themselves, not the antiquities they sell. The aim should be removing criminals from the market, not recovering and repatriating stolen material.

The internet market in antiquities presents a clear and present danger to the survival of the world’s cultural heritage. But it is not a black or clandestine market, it operates in full public view. It is out in the open and almost inviting of monitoring, oversight and investigation. So although the internet market appears to be out of control, it can be brought under control by systematic and sustained policies as recommended here. The challenge is how best to implement them.

Hiscox, “The Hiscox Online Art Trade Report 2016: Bringing transparency to the online art market.” 2016. https://www.hiscox.co.uk/online-art-trade-report/docs/hiscox-online-art-trade-report-2016-v2.pdf.

Deborah Weinswig. “Art Market Cooling, But Online Sales Booming,” Forbes, May 13, 2016. https://www.forbes.com/sites/deborahweinswig/2016/05/13/art-market-cooling-but-online-sales-booming/#13d8476ec9a6.

Neil Brodie. edited by Lawrence Rothfield, “The Western Market in Iraqi Antiquities,” Antiquities Under Siege, (2008), pp. 63-73. Lanham: AltaMira, at 70.

Trocadero. http://www.trocadero.com/.; Vcoins. https://www.vcoins.com/en/Default.aspx.; Invaluable. http://www.invaluable.co.uk/; https://new.liveauctioneers.com/.

Steven Lee Myers and Nicholas Kulish, “‘Broken System’ Allows ISIS to Profit from Looted Antiquities,” New York Times, January 9, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/10/world/europe/iraq-syria-antiquities-islamic-state.html.

Neil Brodie, “Trafficking out of Syria,” Market of Mass Destruction blog, July 27, 2016. http://www.marketmassdestruction.com/trafficking-out-of-syria/.; Neil Brodie, “Last week, the Art Loss Register was endorsing…,” Market of Mass Destruction blog, May 30, 2016. http://www.marketmassdestruction.com/last-week-the-art-lossregister-was-endorsing/.; Neil Brodie, "eBaywatch (1),"Market of Mass Destruction blog, February 19, 2016. http://www.marketmassdestruction.com/ebaywatch-1/.

Charles Stanish, “Forging Ahead”, Archaeology Vol. 62, No. 3, May/June 2009. http://archive.archaeology.org/0905/etc/insider.html.

Mike Giglio, and Munzer al-Awad, “Inside the Underground Trade to Sell Off Syria’s History”. BuzzFeedNews, July 30,2015. https://www.buzzfeed.com/mikegiglio/the-trade-in-stolen-syrian-artifacts?utm_term=.jnpDr3wjx#.jpAj8Qp9R.;Steven Lee Myers, and Nicholas Kulish, “‘Broken System’ Allows ISIS to Profit from Looted Antiquities.” New York Times, January 9, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/10/world/europe/iraq-syria-antiquities-islamic-state.html.

“United States of America v. One Gold Ring with Carved Gemstone, an Asset of Isil, Discovered on Electronic Media of Abu Sayyaf, President of Isil Antiquities Department; One Gold Coin Featuring Antoninus Pius, an Asset of Isil, Discovered on Electronic Media of Abu Sayyaf, President of Isil Antiquities Department; One Gold Coin Featuring Emperor Hadrian Augustus Caesar, an Asset of Isil, Discovered on Electronic Media of Abu Sayyaf, President Of Isil Antiquities Department; One Carved Neo-Assyrian Stone Stela, an Asset of Isil, Discovered on Electronic Media of Abu Sayyaf, President of Isil Antiquities Department.” Civil Action Complaint, December 15, 2016. https://www.justice.gov/usao-dc/press-release/file/918536/download (accessed 18 April 2017), 12-13.

It is noticeable that while the language of choice for most internet dealers and auctioneers is English, or at least a European language, material on social media is often described or discussed in a non-European local language. It might be that social media is being used more to facilitate trafficking than to promote the retail sale of already trafficked objects.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, “ICE, CBP and El Salvador Celebrate Recovery of Pre-Columbian Artifacts in Joint Investigation into Smuggling Ring Selling on E-Bay,” News Release, May 12, 2010. http://www.ice.gov/news/releases/1005/100512washingtondc.htm.