Executive Summary

Working on the very locations of interest to looters, most field archaeologists at some point see for themselves the extensive damage that looting can do to an archaeological site. Indeed, it is not unusual for a field archaeologist to personally encounter looting or evidence of looting activity on multiple occasions across multiple archaeological sites over the course of a career. Archaeologists know that this illegal digging has caused irreparable damage to the archaeological landscape, and that the knowledge they hoped to glean from those sites about the human past has also been compromised, if not lost entirely, by looting. They also know that most countries have criminalized archaeological site looting in their domestic laws. This means that a field archaeologist who witnesses looting firsthand is also, in essence, witness to a crime. Nevertheless, many field archaeologists, by their own admission, choose not to report looting to the appropriate archaeological or law enforcement authorities when they encounter it.

This policy brief draws insights from a global survey on why many field archaeologists say they do not report archaeological site looting when they encounter it, and argues that the duty to report should be a central tenet of a field archaeologist’s professional ethics. It explores the consequences of field archaeologists looking the other way when they encounter subsistence looting, and offers solutions to help archaeologists understand the importance of reporting looting activity when they encounter it in the field.

Introduction

Looting is a globally pervasive problem[1] that has escalated in recent decades,[2] leading many scholars to conclude it has reached epidemic proportions.[3] This policy brief argues that, if practicing and promoting stewardship of the irreplaceable archaeological record is a central tenet of a field archaeologist’s professional ethics,[4] then there exists a duty to report looting when those field archaeologists bear witness to it. Many field archaeologists view the looting they observe to be the work of impoverished locals who have no viable economic alternatives, and out of concern for the welfare of these “subsistence diggers,”[5] they choose not to notify external archaeological or law enforcement authorities.

This paper explores the consequences of field archaeologists looking the other way when they encounter need-driven looting, and urges them to consider for themselves why so many of them choose not to report archaeological site looting when they encounter it. It argues for archaeological organizations and funding agencies to create standardized, enforceable protocols and directives to report site looting, and contends that the subject must play a more formal, central role in professional and academic archaeological education as well as ethics guidelines.

The Archaeologist and the ‘Victim Looter’

Whether in excavation, survey, post-excavation analysis, conservation, or site management, field archaeologists are often the first professionals to encounter never-before-seen site looting—or even looting activity in progress—simply by virtue of where they work. A recent survey asked nearly 15,000 archaeologists working around the world about their personal experiences with archaeological site looting in the field.[6] According to survey results, not only did nearly 80% of archaeologists state they had experienced firsthand encounters with archaeological site looting, but they also noted that these were not isolated encounters.

Most field archaeologists observed looting on more than one occasion on more than a single archaeological site. Not limited to a particular region of the world, type of field project, or type of archaeological site, archaeologists’ personal encounters with looting are frequent, iterative, and widespread. It has become such a commonplace occurrence that, according to one surveyed field archaeologist who has spent most of her career working throughout Cyprus, “[we are taught that] the possibility of meet[ing] with looters while you’re working on site is a given; it’s just a known aspect of archaeological fieldwork.”[7]

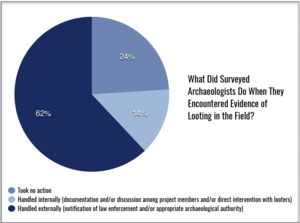

When archaeologists are eyewitnesses to looting in progress or its residual effects on an archaeological site, some archaeologists choose to handle the matter internally, first by documenting the damage and then notifying other archaeological project team members. Other surveyed archaeologists then went a step further in contacting a relevant external agency, which was usually some sort of local archaeological or law enforcement authority.[8] However, nearly a quarter also chose to not report looting activity to anyone at all.

By far, the most common explanation for this non-reporting had to do with the looters themselves.[9] Out of sympathy for the locals doing the actual illegal digging, many, if not most, archaeologists do not report looting to the appropriate external authorities. This concern for the welfare of those doing the illicit digging puts a field archaeologist in an ethical predicament: report the activity, and jeopardize what meager economic gain looting may generate for a host community; or, do nothing, and risk enabling the continued destruction of archaeological resources.

This quandary arises when archaeologists paint looters as victims on two fronts. First, they blame unstable economic conditions for causing some individuals, out of desperation, to turn to looting as a way to make a living. For these archaeologists, the diggers are victims who are “poor, malnourished farmers without money for seed, and without sufficient land to practice subsistence agriculture.”[10] From this perspective, looting motivated by economic despair is justifiable, and “[i]n private, a great many archaeologists are ‘realists’… with a closeted sympathy for the poor indigenous people they hire to work as camp help and grunt laborers.”[11] Second, archaeologists sympathetic to these “victim-looters” also suggest that they are victimized by the broader, insatiable greed—the “lust for antiquities”—of collectors.[12] Arguments have been made that looters are merely “victims of a global market, exploited by the demands and desires of dealers and collectors, who are the real villains.”[13] In this sense, the illegal digging activity of a looter is similarly excused in that it is a simple problem of supply and demand—if there were no demand for antiquities, then there would be no need to loot archaeological sites.

Dismantling the Double Standard

Most countries have domestic statutes that criminalize archaeological site looting. When an archaeologist bears witness to looting, he or she is essentially an eyewitness to criminal activity. Nonetheless, many archaeologists still say they choose not to report looting when they see it, suggesting a double standard, wherein some looters are understood as “victims” and others as “criminals.” That is, some looters are “victims” of both economic despair and the international demand for antiquities, shifting any culpability to the individuals who illegally move, sell, or collect looted items.

Looting motivated by greed is viewed by many field archaeologists as inherently different from looting motivated by need. Indeed, no one disputes that there are distinct criminal dynamics in moving, fencing, selling, and buying unprovenanced antiquities. When investigators discovered that hijacker Mohamed Atta had attempted to peddle stolen Afghan antiquities to help finance the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001,[14] or when looted antiquities in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York were traced back to organized tomb-robbing activities connected to the Italian Mafia,[15] no one thought twice about characterizing those looters as “criminals,” not “victims.” There was no waffling or ethical ambiguity over these sorts of illicit diggers. But this double standard enables the revilement of the antiquities trade in its entirety as a criminally exploitative endeavor, while sidestepping the moral question of criminal responsibility among “victim-looters,” because their need-driven looting is seen as prompted by other people’s greed-driven criminality.

But who are any of us—field archaeologists included—to decide when it is morally acceptable to loot and when it is not? Who is “poor enough” to deserve to loot? Who are we to turn a blind eye to some “types” of looting? The distinction of looters as either exploited victims or exploitative criminals also invites the characterization of archaeologists as eyewitnesses to both criminal activity and victimization. Criminologically speaking, looting is characterized as a matter of both non-reporting of crime and non-intervention with victims, rendering the decision not to report as one potentially of bystander apathy. A non-reporting archaeologist should entertain the possibility that her witness passivity in the face of criminalized archaeological site looting could very well render her an enabler. If an archaeologist is ethically obliged to avoid any action—or in this case, inaction—that might incentivize looting or facilitate the antiquities trade,[16] then an archaeologist must honestly consider the possibility that his or her failure to report could be construed as passive enablement. He or she must also consider that inaction may have the capacity to produce results no less detrimental than would active encouragement of archaeological site looting.

Surveyed archaeologists explained in their own words why they failed to report.

-

“Frankly I’m ambivalent towards looting activities because it is often economic necessity that prompts people to loot archaeological sites.” –Archaeologist #29761

-

“I find it hard to blame the locals, since looted material can bring in over a year or two worth of income, and these people tend to be poor farmers trying to support their families.” –Archaeologist #20734

-

“I did nothing when offered looted items for sale in Peru and Mexico because the items were small and people involved were clearly at the lowest level of the trade.” –Archaeologist #43726

-

“Anyone who is desperate enough to feed their family may resort to such undertakings because the high moral road is simply not an option. I don’t like to put excuses on it, but it is what it is.” –Archaeologist #5977

Policy Implications and Recommendations

Rarely is the act of omission in failing to report a crime or come to a victim’s aid actually considered a criminal act, and there are few laws in even fewer countries that create duties to report for members of certain professions. This does not obviate the archaeologist’s ethical duty to report looting to an appropriate external authority. Whether expressed or implied, reporting duties in criminal law are intended to protect the public welfare. As stewards of the archaeological record as a public good, an archaeologist can reasonably be held to a higher standard of conduct independent of any legally-imposed duty to report looting, simply by virtue of qualifying to practice archaeology. An archaeologist might think twice about the decision not to document or report site looting if he or she were to consider the possibility that inaction—however indirectly—could be a contributing factor to the destruction of cultural heritage.

There are also pragmatic consequences that flow from an archaeologist’s decision not to report site looting. Firstly, non-reporting contributes to the perception that looting is not as pervasive a problem as archaeologists say it is. This plays right into the hands of those who champion an open antiquities trade—namely, collectors and dealers—who insist that the role looting plays in the antiquities trade is grossly exaggerated. Non-reporting also confounds official efforts to measure looting and the extent to which specific transnational markets are fed by it, so the validity of any economic modeling, policy development, or countermeasure based on official data are inherently equivocal.

Perhaps some of archaeologists’ reticence to report site looting is due to unclear professional expectations on how to handle the matter when they bear witness to it. At the very least, as a modest start to any serious consideration of long-term, coordinated anti-plunder strategies, field archaeologists must candidly consider for themselves why so many of them appear to choose not to report archaeological site looting when they encounter it. If the criminalization of looting is not sufficient motivation to report, archaeologists should also consider whether they work in a country with mandatory reporting laws; toward that end, countries which have criminalized looting but are without such mandates could also consider establishing and enforcing them. Perhaps any and all field permits issued should also include language pertaining to looting and what archaeologists might expect to do about it should they encounter it.[17] Information on any looting activity should also be documented and included in any and all field reports, and principle investigators (PI’s) should consider developing and discussing with field season staff their own more specific plans of action for how to safely handle looting or encounters with looters during field seasons.

Such proactivity among archaeologists is not limited to the field. The duty to document and report looting should also play a more central role in the discussion of archaeological ethics in academic classrooms. A cursory examination of some popular introductory archaeology college textbooks reveals that the subject of archaeological site looting is treated somewhat generally if not superficially, and archaeologists’ responsibilities in the field is nowhere specifically discussed.[18] Based on lacunae such as these, it is no wonder that there is some ethical ambiguity as to what a field archaeologist might do when bearing witness to site looting.

Furthermore, it may be helpful for professional archaeological organizations and field projects to clarify expectations for their members regarding looting. The World Archaeological Congress (WAC), for example, provides ethical guidance in its First Code of Ethics, but nowhere therein is archaeological site looting explicitly referenced, let alone a field archaeologist’s responsibility to report it.[19] Similarly, the Society for American Archaeology (SAA) notes the relationship between site looting and the commercial exploitation of the archaeological record, but only broadly directs archaeologists to avoid “activities that enhance the commercial value of archaeological objects.”[20] If an archaeologist chooses to turn a blind eye to what she perceives as need-driven looting, she must concede that doing so acknowledges the potential commercial value of a looted antiquity.

Some professional organizations’ codes of ethics appear to be more specific regarding the archaeologist’s obligations toward the reporting of site looting. The Archaeological Institute of America (AIA), for example, has since 1990 directed its members to “Inform appropriate authorities of threats to, or plunder of archaeological sites.”[21] Similarly, the European Association of Archaeologists (EAA) states, “It is the responsibility of archaeologists to draw the attention of the competent authorities to threats to the archaeological heritage, including the plundering of sites.”[22] On the other hand, the Register of Professional Archaeologists (RPA) states that “Archaeologists shall not knowingly be involved in the recovery or excavation of artifacts for commercial exploitation, or knowingly be employed by or knowingly contract with an individual or entity who recovers or excavates archaeological artifacts for commercial exploitation”[23] and that “An archaeologist shall report knowledge of violations of this Code to proper authorities.”[24] Taken together, this RPA language seems to indicate that archaeologists should not work with individuals known to participate in looting, but there is no guidance provided on what archaeologists should do regarding local looters unaffiliated with a field project.

As evidenced in the few examples provided above, the language in archaeological organizations’ codes of ethics regarding looting and the degradation of archaeological sites varies greatly. Archaeologists should at minimum recognize that the variability among their organizations’ codes of ethics could be sending mixed messages about how their members might handle looting when they encounter it in the field. And certainly, despite what language may exist in an organization’s code of ethics, there are member archaeologists who do not at all feel ethically obliged to do anything about looting. Certainly, issues of looting and archaeological site destruction are nuanced, locally contingent happenings that do not occur in a cultural vacuum. In that sense, it seems unrealistic if not unreasonable to suggest that organizations should embrace one sweeping, universal directive on how archaeologists should handle looting encounters within the local cultural context where they work. Perhaps, then, organizations should implement language in their respective codes of ethics that is aspirational rather than prescriptive in nature.[25]

Finally, as archaeology has largely moved beyond a public outreach model to one of community-oriented archaeology,[26] archaeologists should consider the cultivation of a host community’s ownership over local archaeological resources an integral component of fieldwork. It is, frankly, more difficult for anyone to care about the preservation of their own cultural heritage if they feel no personal connection to or stake in it. Such efforts may also help communities play a more central and active role in local archaeology.

Conclusion

As experts in their field, it matters what archaeologists do or do not do about looting. The act of omission in failing to report a crime or come to a victim’s aid is rarely a legal matter, but as argued in this paper, the field archaeologist has an ethical duty to do so. This imperative to deal with archaeological site looting is created by both archaeologists’ commitment to preservation, as well as their unique position as potential eyewitnesses. Archaeologists the world over denounce looting as a criminal offense, but it is difficult to take this seriously if many archaeologists on the scene do not themselves choose to treat it as such. Therefore:

-

Professional archaeological organizations should clarify their members’ duties to report looting.

-

In countries which have criminalized looting, whether or not there exists a specific mandatory reporting directive, archaeologists should consider seriously the implications of non-reporting crime.

-

PI’s should consider developing a plan of action with field project members on how to handle looting, and any incidents of looting should be documented and recorded as part of field reports.

-

Field permits issued should include language pertaining to looting and what archaeologists might expect to do about it should they encounter it.

-

Archaeologists’ ethical duty to report looting should play a central role in undergraduate and graduate archaeology curricula and classroom discussions.

-

Field archaeologists should engage in public and frank discussions about looting with local communities in the field.

Damage to the archaeological landscape is not dependent on whether looting is motivated by greed or need. Neither is it dependent on an archaeologist’s motivations for non-reporting. When archaeologists are next met with looting in the field, they might do well to seriously consider the far-reaching ethical and legal implications of choosing inaction.

There are likely as many unknown archaeological sites around the world as known ones, so it is impossible to determine just how much of the archaeological record has been damaged by site looting. Nonetheless, a large body of research on looting assesses the extent of known site damage and destruction. For example, of the 550 ancient Etruscan tombs discovered in Italy, one study estimated that nearly 400 of them had been looted. Surveying ancient Lydian tombs in Turkey, another research team found that 90% of them showed signs of having been looted. In Peru, it is believed that every single site known to archaeologists to date has been affected by looting. See Lerici, C. (1969). The Future of Italy’s Archaeological Wealth. Quoted in Meyer, K. (1973), The Plundered Past. New York: Atheneum; Roosevelt, C. & Luke, C. (2006). Looting Lydia: The destruction of an archaeological landscape in western Turkey. In Brodie, N, Kersel, M, Luke, C, & Tubb, K (Eds.); Archaeology, Cultural Heritage, and the Antiquities Trade. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida; Alva, W. (2001). Destruction of the archaeological heritage of Peru. In Brodie, N., Doole, J. & Renfrew, C. (Eds.), Trade in Illicit Antiquities: The Destruction of the World’s Archaeological Heritage,pp. 89–96. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

See Brodie et al. (2001). Trade in Illicit Antiquities: The Destruction of the World’s Archaeological Heritage. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

See Hoffman, 2006; McAlister, 2005; Brodie, N. (2002). Introduction. In Brodie, N. & Tubb, K. (Eds.) Illicit Antiquities: The Theft of Culture and the Extinction of Archaeology; Brodie 2000; O’Keefe, 1997.

See, for example, the Society for American Archaeology’s Principles of Archaeological Ethics #1: “The archaeological record, that is, in situ archaeological material and sites, archaeological collections, records and reports, is irreplaceable. It is the responsibility of all archaeologists to work for the long-term conservation and protection of the archaeological record by practicing and promoting stewardship of the archaeological record. Stewards are both caretakers of and advocates for the archaeological record for the benefit of all people; as they investigate and interpret the record, they should use the specialized knowledge they gain to promote public understanding and support for its long-term preservation.”

Bowman Proulx (2013), “Archaeological site looting in “glocal” perspective: Nature, scope, and frequency,” 111-25.

2,358 online surveys were completed, which provided quantitative data for regression analysis. The survey’s open-ended questions as well as follow-up interviews yielded an additional 3,009 pieces of qualitative feedback for emergent analysis. See Bowman Proulx (2013), “Archaeological Site Looting in “Glocal” Perspective: Nature, Scope, and Frequency,” 111-25.

Bowman Proulx, “Archaeological Site Looting in “Glocal” Perspective: Nature, Scope, and Frequency,” 111-25.

In some countries, for example, the notified agency was a specialized police unit tasked specifically with cultural heritage protection (e.g., Italy’s Comando Carabinieri per la Tutela Patrimonio Culturale); in others, it was a local unit of an independent archaeological authority (e.g., Greece’s Archaeological Service, which has nearly 50 departments located throughout the country that, among other things, supervise local archaeological projects).

This was not the only explanation proffered by surveyed archaeologists. Other justifications included the futility of reporting to external authorities (e.g., local archaeological or law enforcement authorities are ill-equipped, indifferent, or in some cases, themselves looters) and self-interest (e.g., career-driven concerns to preserve relationships with host communities, fieldwork opportunities, and research productivity). For a comprehensive discussion of these rationales, see Balestrieri, Blythe A. (2018). “Field archaeologists as eyewitnesses to site looting.” Arts 7(3): 48.

Matsuda, D. (1998). The ethics of archaeology, subsistence digging, and artifact looting in Latin America. International Journal of Cultural Property7(1): 87-97.

Ibid.

Muscarella, O. (2009). 'The fifth column within the archaeological realm: The great divide," in Studies in Honour of Altan Cilingiroglu: A Life Dedicated to the Urartu on the Shores of the Upper Sea. Ed. H. Sağlamtimur, et al., Istanbul: Arkeoloji ve Sanat Yayınları, 2009: 395-406. March 2020 | No. 6 10 POLICY BRIEF SERIES.

Hollowell, J. (2006), ‘Moral arguments on subsistence digging’, in Christopher Scarre and Geoffrey Scarre (eds.), The Ethics of Archaeology: Philosophical Perspectives on the Practice of Archaeology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 69-93; Elia, Ricardo J. 1993. A seductive and troubling work. Archaeology 46: 64–69.

de la Torre, L. (2006, Feb 20). Terrorists raise cash by selling antiquities. Government Security News 4(3). Retrieved November 15, 2006 from: http://www.gsnmagazine.com/pdfs/38_Feb_06.pdf.

Stille, A. (1999), ‘Head found on Fifth Avenue: Investigators finally think they know who’s been taking the ancient treasures of Sicily’, The New Yorker, LXXV (12), 58-69.

Brodie, N. (2008). “Cultural heritage and human rights: A critical view.” Roundtable discussion at the American Anthropological Association 2008 annual meeting, November 19-23, 2008, San Francisco, CA.

Some funding agencies do not feature any language at all on archaeological site looting whatsoever, let alone what a funded project might do about it; others indicate that funded projects should comply with ethical standards, but lack explicit language or specific direction on the duty to report or at minimum document looting. For example, a cursory review of grant application information posted by the Archaeological Institute of America, the National Science Foundation, the Social Sciences Research Council, the Volkswagen Foundation, and Fulbright provides no guiding language for grant applicants to include information on or a plan of action to deal with the possibility of site looting on a funded project. On the other hand, grant applications submitted to the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) are required by the National Historic Preservation Act to consider the potential effects a project might have on the preservation of an historic property. While looting could be taken to mean one such potential effect, it is not explicitly stated as such. See “Frequently Asked Questions About Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act,” National Endowment for the Humanities, https://www.neh.gov/grants/manage/frequently-asked-questions-about-section-106-the-national-historic-preservation-act (accessed August 7, 2019).

For example, Renfrew & Bahn’s Archeology: Theories, Methods, and Practice addresses looting and the antiquities trade (pp. 299-315) and identifies looting as a contributing factor to the destruction of archaeological sites (p. 317), but does not recommend any steps an archaeologist should take when she witnesses looting firsthand in the field. Greene and Moore’s Archaeology: An Introduction discusses the antiquities trade as an ethical issue (pp. 180-1), but never addresses the subject of looting or a field archaeologist’s responsibility to report it. In covering the legislative history of archaeological site preservation in the United States, Carver’s Archeological Investigation notes that it is formally the responsibility of the federal government to protect such sites, but provides no discussion as to what a field archaeologist should do upon encountering looting in the field. See Renfrew, Colin, and Paul G. Bahn. Archaeology: Theories, Methods and Practice. 7th ed. London: Thames & Hudson, 2016; Greene, Kevin, and Tom Moore. Archaeology: An Introduction. 5th ed. Oxford: Routledge, 2010; Carver, Martin. Archaeological Investigation. Oxford: Routledge, 2009.

As of March 2012, the WAC has a Standing Ethics Committee, whose current business includes the development of a general code of ethics for the WAC as well as an international code of archaeological ethics. See “Code of Ethics,” World Archaeological Congress, https://worldarch.org/code-of-ethics/ (accessed August 7, 2019).

“Ethics in Professional Archaeology, Principle No. 3: Commercialization,” Society for American Archaeology, https://www.saa.org/ career-practice/ethics-in-professional-archaeology (accessed August 7, 2019).

“Code of Ethics, Principle No. 4,” Archaeological Institute of America, https://store.archaeological.org/sites/default/files/files/ Code%20of%20Ethics%20(2016).pdf (accessed August 7, 2019).

“EAA Code of Practice, Archaeologists and Society, Principle No. 8,” European Association of Archaeologists, https://www.e-a-a.org/ EAA/About/EAA_Codes/EAA/Navigation_About/EAA_Codes.aspx?hkey=714e8747-495c-4298-ad5d-4c60c2bcbda9#practice (accessed August 7, 2019).

“Code of Conduct, Section 1.2(J),” Register of Professional Archaeologists.

“Code of Conduct, Section 2.1(G),” Register of Professional Archaeologists.

See, for example, the Statement of the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) Policy on Preservation and Protection of Archaeological Resources, available online at: http://www.asor.org/initiatives-projects/asor-affiliated-archaeological-projects/standardspolicies/asor-policy-on-preservation-and-protection-of-archaeological-resources/.

Sometimes referred to as “public archaeology,” community archaeology aims to collaborate with local and descendant communities in the design and implementation of archaeological research projects. See Atalay, S. (2012), Community-Based Archaeology: Research with, by, and for indigenous and local communities, 1st Edition. Berkeley: University of California Press.